Reptile & Amphibian

News Blog

Keep up with news and features of interest to the reptile and amphibian community on the kingsnake.com blog. We cover breaking stories from the mainstream and scientific media, user-submitted photos and videos, and feature articles and photos by Jeff Barringer, Richard Bartlett, and other herpetologists and herpetoculturists.

Friday, August 9 2013

Steel CONEX containers would be the perfect mouse shacks, if the sun didn't have a habit of turning them into gigantic ovens. But with a little ingenuity, a small air conditioner, and a reasonable amount of insulation you can quickly turn that oven into something cold enough to store meat in, even in the Texas sun.

CONEX boxes are available in many different types and sizes from gigantic 40-foot monsters down to tiny 6- or 8-foot units. Some are designed as cooler units, referred to as "reefers," but most are just giant steel boxes designed to carry goods in bulk around the world as deck cargo on ships, trains, or trucks.

The price varies, but used reefer units are generally out of the reasonable price range with 20-foot units going for $6000-$9000. A standard, non-leaker, used 20-foot CONEX box can usually be located on Craigslist for around $2000-$2500, and can be moved by most flat bed tow trucks a reasonable distance for $100 to $150. Larger, and heavier, 40-foot units usually require a specialized delivery truck, a lot more room, and a lot more money.

We found our CONEX box locally on Craigslist for $2100, and had a tow truck deliver it to our site for $150. Our unit came with passive louvered vents on the front door and the rear, although most do not. Once the unit was in place, we made the first of what would be many trips to Home Depot. There we bought a small window A/C, an inexpensive pre-hung interior door, some 2x4s and a number of 1/2- and 3/4-inch 4x8 reflective exterior insulation panels. And duct tape. Lots of duct tape.

With an active vent louver from Amazon.com and a box fan and a Sawzall reciprocating saw from the shop, we set about modifying the CONEX box. First, we removed the existing vent from the rear of the unit, then we expanded its hole using a metal cutting blade on the Sawzall. Though the steel is 1/4-inch thick, the reciprocating saw had little difficulty cutting though it. Once the vent hole was expanded, we cut another hole below it for the air conditioner. Bracing it with wood on the inside, we installed the A/C, making sure that the intakes were reaching the outside.

The vent hole we started with was larger than our active went louver, so we had to make a 2x2 wooden plate to cover the gaps. Once installed, and tested with a fan, the louvers popped right open like designed. Hooked up to a timer, the ventilation fans will come on from 10 pm to 8 am, automatically opening the louvers and venting the mouse room of any built up ammonia for 8 hours. The louvers will close when the fans turn off and the A/C runs, from 8 am to 10 pm.

Thursday, August 8 2013

Being more an amphibian person than a reptile person, on the first of my many trips to Amazonian Peru the anuran I wished most to see was Atelopus spumarius, the Amazon harlequin frog. When I told our Peruvian guides C-sar and Segundo this they had no idea what I was talking about for firstly, most of the tour clients who visited were snake enthusiasts and secondly, I had no idea what the local name for Atelopus was. So I came up with a name that I thought might help; Ranita Pintada, little painted frog. Despite walking through rainforest that seemed ideal I zeroed out. Wondering why, the finding of Atelopus became nearly an obsession.

The next trip down there I was better prepared. I brought a picture with me. Still neither Segundo nor C-sar recognized the frog, but now they knew what I was hoping for, and being astute guides, they headed to the back of the preserve. That day, along the long trail, they found not one but two of this coveted species. Couldn't be any better than that.

Wednesday, August 7 2013

Whether you're breeding 100 mice or 10,000, setting up your breeding facility correctly at the beginning can prevent a lot of problems and heartbreak down the road.

If you can think of a problem, it has happened to someone before, in many cases with disastrous consequences. No one wants to come home from vacation to find that your rodents are floating down the hallway and you've made the 6 o'clock news.

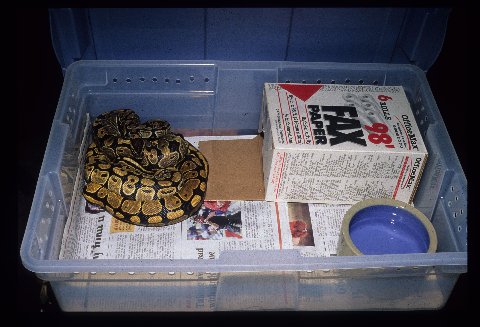

First, you need to determine your needs, as this will set the size of the breeder colony you need and the space and caging required. We've already determined that we will need to produce at least 8,000 mice in a 12-month period. A mouse's reproductive cycle is roughly 20 days, and then they are immediately ready to breed again. We will need at least 1000 litters in 12 months. Rounding up to 30 days between litters, we need to produce 84 litters per month to reach that number, or in plain numerical terms 84 producing females.

The number of males required will be set by the total number of mice each cage will support. For our cages we'll be using one male for every three females in each cage, so we will need at least 28 males. Larger tubs, such as bus tubs, usually support larger groupings of between six and eight mice. In a perfect world we would need 112 mice total to keep our colony fed for a year, along with caging, food and water, and other basics.

However...

Because mice are horrible at math, and nature is unpredictable...

We will base our first mouse colony on having 200 mice, in 50 cages. That will provide for a backup in case of slow production, cycling of new and retired breeders, and insurance against accidental losses. Hopefully it will provide a small backstock of over-production and allow for rapid expansion when the time comes.

Housing 200 mice is something you don't want to do in your house, or worse, your apartment. The risks of cross contamination are simply too great. In a best case scenario all animals, mice included, should be sited in a separate outbuilding, ideally one that can be decontaminated if not sterilized. While people have been using wooden buildings to breed mice for years, if you're starting from scratch there are other better options to consider.

Many breeders use steel sheds, others use custom metal buildings. We chose a 20-foot steel CONEX shipping container. With only a wooden floor that can be removed and replaced as needed, it's almost the perfect solution. Almost.

Tuesday, August 6 2013

Because of some strange compulsion, I had decided that I wanted to photograph the very variable yellow rat snake from every Florida county in which it occurred. This quest would take me roughly over four-fifths of the peninsula, excluding only the northernmost and northwesternmost counties.

Just two nights earlier, with Mike Manfredi, I had started my search of Lake County. An afternoon shower had left the grasses and shrubs spangled with twinkling droplets but the pavement was now dry. Traffic was very light. The sun had dipped nearly to the western horizon but what had promised to be a beautiful sunset had been obscured by an almost solid cloud cover. Within minutes after sunset natricines (water, crayfish, and ribbon snakes) began crossing the road. But no rat snakes, yellow or otherwise, had made an appearance.

That night I was accompanied by Jake Scott. Climatic conditions were a bit different. Roadway and vegetation were both dry and rather than being obscured by a cloud cover the stars twinkled above. The moon was just peeping above the horizon. We made a couple of passes over the 10 mile stretch of road. Traffic had been light but now a car was quickly approaching us. I was watching the oncoming vehicle when Jake hollered "Snake! Yellow!"

Monday, August 5 2013

With a projected 200 kingsnake cages to start with, securing the food source is probably the most important first step in my business plan. Before I even began to hunt for my breeder snakes, I wanted to have a primary and secondary food source in place.

Kingsnakes and milk snakes are ravenous feeders that will eat a variety of prey items, from rodents to reptiles, so that makes it relatively easy to find a food source. Availability, price and delivery can make this a costly proposition, however, especially on a commercial scale.

When I started as a hobbyist, finding a feeder mouse or two wasn't difficult, but finding enough to feed 20 or more animals on a regular basis was problematic. To feed a collection of size you invariably had to start your own mouse colony.

Today, a hobbyist or breeder can choose from a variety of sources, from individually-wrapped frozen feeders at the chain pet stores Petco and PetSmart, or bulk frozen feeders from a local pet shop. Frozen feeders are almost always available in bulk at the many reptile expos that occur across the country every year as well, supplied by the dozens of local breeders. And feeder mice are also available in uncounted places on the internet, from massive breeders like RodentPro, Mice Direct, and Big Cheese Rodents, to smaller local breeders advertising in kingsnake.com's classifieds. Frozen feeder mice are even available on Amazon.com!

If you want to save yourself space, convenience, labor, smell, and a variety of other issues, hazards, and problems, buying frozen feeder mice is really your best option.

If, on the other hand, you plan on starting and building a massive colony of breeder snakes as we are, the costs of buying frozen feeders can be daunting. With an estimated 200 colubrid snakes consuming a minimum of 1 mouse a week, 40 weeks a year, we will need to have on hand 8,000 feeder mice over a year's time. So in our case, our best option is to start our own mouse colony.

Friday, August 2 2013

Three teeny-weenies unexpectedly pipped and emerged from some eggs that I had thought, until the event, had no chance of hatching.

Fact is, the eggs, a clutch of six, all looked bad. All were discolored, windowed, and shriveled. Although as I do with all clutches I moved these eggs to an incubator, it seems that I was so disappointed in their appearance that I promptly forgot them.

Then fifty days later, when checking the progress of a clutch of diamond-carpet python eggs in that incubator, from one of those “no chance” eggs a tiny reddish head protruded. And although the three top ones were obviously dead, two others on the bottom tier had pipped.

I was sure glad then that I hadn’t tossed that clutch. Twenty-four hours later, all three of these little brick red snakes with reddish brown blotches had fully emerged.

Thursday, August 1 2013

Reptile and amphibian hobbyists, breeders, academics, researchers, and zookeepers from around the globe are converging on the Astor Crown Plaza in New Orleans, Louisiana, this week for the 36th International Herp Symposium.

Starting with an icebreaker Wednesday night, followed by three days of presentations on herpetology, herpetoculture, and reptile veterinary medicine, the event also includes swamp tours in an airboat, a banquet and keynbote by Australian herpetologist John Cann, a silent auction, and more. Additionally, all attendees are invited to free admission to the Audubon Zoo, the Aquarium of the Americas and the Audubon Butterfly Garden and Insectarium in New Orleans.

While the call of Bourbon Street may be tough to ignore, there will be dozens of cool reptile and amphibian presentations over the next few days to keep herpers out of the bars, at least during the day. Some of the world's leading herpetologists, herpetoculturists, veterinarians, and more are scheduled to present at this year's event, guaranteeing something for every herper's interests. For a schedule of the IHS presentations, check out the IHS website.

I will be giving a presentation on reptile and amphibian laws on Friday at 4:45pm. My 30 minute presentation, titled “Reptile Laws: The role of NRAAC and NGOs in the Reptile & Amphibian Regulatory Process,” will be a quick overview of the NRAAC organization, and other organizations, and how they are involved in the creation of laws and regulations at the federal, state, and international levels. It will also discuss the upcoming NRAAC Reptile & Amphibian Law Symposium in Washington D.C. in November.

For more information on the NRAAC Reptile & Amphibian Law Symposium please visit the NRAAC website.

Wednesday, July 31 2013

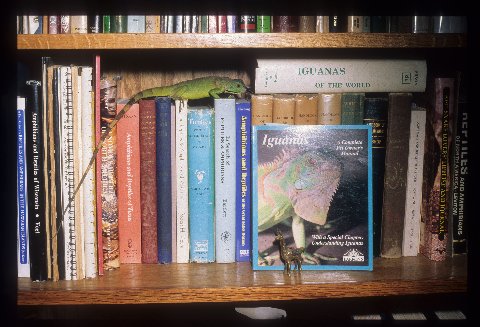

The availability of captive-bred reptile and amphibian species to work with today is almost endless, with new color phases and morphs being discovered or created all the time.

Back when I was a hobbyist in the 80s and 90s, only a few species were being produced in captivity, primarily native colubrid snakes along with a small handful of exotics. The other species available, especially the exotic species, were almost invariably wild-caught imports, and even such animals as Honduran milk snakes, common in the captive-bred community today, were only available as parasite-infested wild-caught specimens whose survival was often questionable. Sports, or morphs, were virtually unknown, albinos truly rare, piebalds a holy grail.

With all the choices available today, just how do you pick which reptile or amphibian species to work with?

No matter what your interest is, there is something available for you, and that's the first place to start: your interests.

Certainly there are other factors involved, not the least of which are space, cost, legality, etc., that all must be considered, but in the end, if you're not interested in the species or morph, why work with it? Whether you want to work with Pacman frogs because you like Pacman frogs, or you want to chase the rainbow by breeding the latest and greatest ball python or hognose morphs, if you're not working with something you're interested in, you might as well be delivering pizzas instead.

My interests have been, and always will be, kingsnakes and milk snakes, and because that also happens to be the "branding" chosen for this web site long long ago, it's a natural that I've started by breeding kingsnakes and milk snakes. With relatively easy care requirements, and a variety of species, sub-species, and color morphs to work with, they make excellent examples of "first time breeder" animals, one for which a ready market exists.

My business plan calls for acquiring several hundred kingsnake and milk snake hatchlings over the next 24 months, along with a few select adults, raising them up, breeding them, and then selling their offspring primarily into the wholesale market. As such it will be a full three years before I can expect to see any offspring in salable quantities, or the first returns on the investment, and as such will have to make very careful and wise decisions and good deals.

I plan to work primarily with less expensive snakes to start, California kingsnakes, eastern kingsnakes, Pueblan milk snakes, and a few others, avoiding the more problematic feeders or more collectible species such as graybanded and moutain kingsnakes, as well as avoiding the "man-made" morphs and sports such as albinos. Later as the operation expands I'll look at adding more variety, but for now I'm going to focus on basics.

If you have these on your table at a show this year, or have them posted to our classifieds here, don't be surprised to find me checking out your stock.

If you started a commercial reptile breeding business, what species would you choose, and why?

Tuesday, July 30 2013

I’m never quite sure, when I first take the dogs out early in the morning what backyard visitor I’ll encounter. It could be a raccoon, an armadillo, a grey fox, a feral cat -- or an alligator.

Alligators of various sizes often wander through the yard. They might come from the pond down the hill heading for the wide open spaces of Paynes Prairie State Preserve. Or for reasons best known to them, they may leave the comparative vastness of the Prairie (especially during drouth conditions) and aim towards the downhill neighborhood pond.

Many of the gators seem to make it as far as our yard and then take a break for an hour (or a day) before continuing their journey. If they’re small we try to see them safely across the roadway, carrying them in whichever direction they seem to be heading. If they’re large we wish them well, but they must journey at their own speed.

Monday, July 29 2013

It's been a long while since I've kept a breeding colony of anything, so it was a surprise even to myself when I heard the words "I'm starting a commercial breeding colony of kingsnakes this year" coming from my mouth earlier this spring. Some of my friends thought I should have my head examined.

I had long ago swore off "keeping" as an addiction that in my position could easily, and quickly, spiral out of control, yet here I was making plans for exactly that, except on a larger scale than I had ever attempted as a hobbyist some 20-odd years ago.

At least this time I'd be going at it with a plan, of sorts, and a direction, rather than just buying or catching the things I thought were "cool." And now there was an industry to support my endeavor, rather than a scattered grouping of friends and a handful of reptile events.

Yeah, a lot has changed since I was a hobbyist keeper the first time. There are many more captive-bred species available, the Internet is now a vast communication network that everyone uses rather than just an odd few techno geeks, and many of the technologies and gear that hobbyists had to develop and build by hand are now readily available as quality manufactured items.

And reptile breeders are much more professional and businesslike in their approach than 20 years ago, as well. On top of that, there is much more knowledge and information available than ever before. And I have had 20+ years to learn from my, and others', mistakes.

Putting this all together should be easy, right? I'll be documenting it here, so stay tuned and find out!

Friday, July 26 2013

By

Fri, July 26 2013 at 06:08

This time of year, a lot of herpetoculturists focus on the "cleidoic egg," the name given to the reptile egg. The cleidoic egg allows reptiles (and birds) to reproduce away from standing water because it encapsulates the necessary fluids needed for embryo development in a nice porous shell useful for proper gas exchange (without leaking moisture).

As with many reptile breeders, I have many thoughts on proper egg incubation. I have tried any number of media for egg incubation; I have tried various temperatures using incubators or even incubating eggs at room temperature.

The one conclusion I've reached: If the egg is fertile and the shell is well developed, the egg will hatch no matter how it is incubated. This holds true for most colubrid eggs. I realize that certain reptile species, like some pythons, may need modified egg incubation, but, I'm going to stand with this statement for most other reptiles.

That being said, there is a lot that the herpetoculturist can do to mess up their ward’s eggs. My number one "mess-up" is improper care of the adults prior to receiving the egg. Not enough food, wrong brumation temperatures, and incorrect nest box are just a few of my many errors.

A happy time of year is depicted in the following image:

This Mexican Hognose Snake is laying her eggs in her nest box. And yes, I use paper towels, not moss in the nest box. That requires proper monitoring of moisture ensuring the medium does not dry out (yet another one of my mess ups).

Thursday, July 25 2013

Well, actually, it takes more than a bit of rain to get the gopher frogs, Rana capito, up and moving. Truth be told, a bit of rain may get them near the mouths of the burrows in which they are usually secluded, but it takes a whole durn-lot of rain to get them out of and beyond their entryways.

The gopher frog may be the most seldom seen of the “common” southeastern frogs. A species of sandhill ponds, it spends a goodly percentage of the daylight hours an arm’s length or further back in the burrow of the gopher tortoise. When in the ponds the snoring calls of the gopher frog are unmistakable.

Like most frogs, the gopher frog is capable of considerable color change. Often having a ground color of light tan to light brown with irregular dark spots and bars when warm, they darken considerably when cold. When cold they may be nearly black. Then the darker markings are all but indiscernable.

Wednesday, July 24 2013

We're used to drop-ins at our place, and last week was no exception. A 30-inch gator took up residence in the small frog pool we dug on the unfenced north end of our yard.

We live about a half mile from a large pond, fed by a small creek. Once in a while a good-sized gator is on the losing side of a nocturnal territory dispute and leaves the pond as a result.

We've had 8-footers in our yard twice. Once or twice during daylight hours we've seen smaller gators, about 4 feet long, stalking with great dignity alongside Williston Road, a busy street that separates our yard and the large pond from Payne's Prairie. But this is a losing stroll; busy roadways and wandering gators don't mix. A few may make it across; the next day all we see are the flattened corpses of those that don't.

Although they have been amazing prolific, it is still hard to be an alligator in Florida. Human invaders have taken over lakeside/riverside properties and their yappy dogs/sunning housecats are no match for a gator's jaws. Homeowners are nervous about gators, but dry land unprovoked attacks on humans are extremely rare. Alligators seem to sense human contact is to be avoided. But when the young gators grow too large to be tolerated by the resident bull gators, territory disputes result and the loser has to leave. Will he find a place to live before he wanders across a roadway? It's a race against time, stacked against the gator.

"Help" is available. The state has a program to deal with what's called nuisance alligators, those four feet or longer that are considered to be dangerous by the individuals who call the state's wildlife hotline. A licensed alligator trapper is summoned to haul away said gator. That gator, poor thing, becomes the property of the trapper. The "property" turns into meat and a tanned skin, a source of income for the trapper.

We discovered our latest too-small-to-be-a-problem gator late one afternoon when we walked up the hill to see how the new sod rimming the frog pool was faring. Centered in the pool, splayed to keep himself as inconspicuous as possible and circling to keep us in sight, was a thin, small gator. He obviously found us disquieting. The problem was space; the pool he had "discovered" was just 15 feet in diameter and maybe a foot deep. The pool wasn't large enough to offer enough cover to a hatchling gator, much less to this guy, who we guessed at maybe two years old. (A foot of water doesn't provide any invisibility to a creature whose survival depends on not being seen.)

We thought about where to relocate him (we know more about nearby bodies of water that he would, obviously) , but in the meantime hospitality won out and we offered comfort food. This was in the form of two dead white mice, tossed in the pond under cover of darkness. The impact of mice on water resulted in an agitated thrashing on the part of the gator.

Our visit and the mice evidently proved to be too much of an intrusion. Next morning the gator was gone and the untouched mice were still near the water's edge. I haven't had the heart to check Williston Road.

Tuesday, July 23 2013

Changing habitat conditions have also taken a toll on the southern populations of the marbled salamander, Ambystoma opacum. I know this from personal experience.

Both Bishop ( Handbook of Salamanders) and Conant ( A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern North America) (1947 and 1958 respectively) showed the range of the marbled salamander extending southward on Florida’s Gulf Coast to Tampa Bay. That it extended at least that far south in the mid 1960s is a certainty for Ron Sayers, and I found adults and metamorphs of this beautiful mole salamander under discarded ties beneath a railroad bridge in Lithia Springs.

Between then and today (2013), this still-widespread eastern taxon seems to have lost its foothold on the Florida peninsula, but is still known to occur in suitable habitats on the Florida panhandle. The range of the marbled salamander along the eastern seaboard no longer seems to extend south of southeastern Georgia.

Friday, July 19 2013

Drought? Development? Climate changes? Other? Or all of those causes listed? I don’t have the ability to assign a cause or causes, but I do know that over the last six decades (since I have been active in the field), the southernmost ranges of at least two amphibian species -- the marbled salamander and the ornate chorus frog -- have been dramatically altered.

In the range maps of the 1958 edition of A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern North America, Roger Conant, meticulous for accuracy, showed ornate chorus frogs, Pseudacris ornata, south along both coasts of Florida to the latitude of Lake Okeechobee.

Since I had never found this frog south of Bradenton on Florida’s Gulf Coast (and had never looked for it on the Caribbean Coast), I queried Mr. Conant about the statement made that the frog was found “through most of Florida."

Tuesday, July 16 2013

A group of us had just seated ourselves for lunch at the dining area of Madre Selva Biological Preserve on the Rio Orosa of Amazonian Peru. We had spent most of the morning photographing herps and were discussing what trails we would walk following the meal. A few yards down slope were the waters of a small, quiet inlet.

Suddenly, all talked stopped. A small Suriname toad, Pipa pipa, had just surfaced in the center of the inlet. Action was nearly immediate. Segundo went out one door shedding clothes as he ran. Ian ran out another door. The contest was on. May the best (or at least the fastest) man win!

Segundo hit the silted water from one side and Ian from the other, but either Segundo’s leap had been longer or the toad had been a bit closer to his launching point. When he left the water Segundo was gently clutching the toad, one of the strangest of Amazon amphibians.

Monday, July 15 2013

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has proposed a blanket National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) exclusion for itself under the Lacey Act. What does that mean?

NEPA requires USFWS, and all federal government agencies, to prepare environmental assessments and environmental impact statements. In other words, scientific and procedural due diligence must be completed before any species can be listed as injurious. An exclusion from this process would essentially make it much easier for USFWS to list species as injurious, which would end importation and interstate commerce for any species listed.

Currently, FWS can declare a categorical exclusion for anything it likes. That doesn't mean a court will agree the action is exempt from NEPA analysis. However, this adjustment to the Department of the Interior’s Departmental Manual would strengthen the legal basis for using a categorical exclusion.

This affects much more than large constricting snakes and much more than herps. This would affect many segments of the pet industry, especially the aquatic (fish) segment.

The negative economic impact could be huge. Just imagine if interstate commerce was illegal for ball pythons, boa constrictors, Pacman frogs, White’s tree frogs and Crested geckos.

It takes just a few minutes to express your opinion. After you complete the actions, share it with others in the herp community and pet owners. USARK has made it very easy to make your voice heard. Surely you have just 5-10 minutes to support your herp community, your friends and your colleagues.

USARK Action Alert can be found here.

Continue reading "USFWS Categorical Exclusion from NEPA: What does it mean?"

Thursday, July 11 2013

It is always cause for comment when with the advent of warm nights the Mediterranean geckos, Hemidactylus turcicus, are drawn from their places of winter seclusion to forage on our house and sheds.

During some springs only one or two geckos initially appear; other years the lizards appear en masse, with every illuminated window disclosing one or more newly emerged foraging gecko. On those nights the life of every light-drawn small moth or beetle is in precarious straits. Patti and I sit and marvel at their adroitness on windows and walls, mostly outside, but occasionally finding their way through a nook or cranny yet unknown to us, or an open door to visit temporarily indoors.

In bygone years the Mediterranean gecko (also referred to as the Turkish gecko) was an abundant exotic that was distributed widely over much of the Florida mainland from the Keys northward to Tampa Bay and Vero Beach. It was more locally distributed in and beyond north Florida. Today it may be encountered in protected areas across the southern USA and is slowly expanding current ranges northward. But while expanding north of Florida, it had run into serious competition in South Florida, first from the parthenogenetic Indo-Pacific House gecko and now from the larger and seemingly more prolific Amerafrican House gecko.

Tuesday, July 9 2013

There are on the Lower Keys of Florida three species of tiny geckos of the genus Sphaerodactylus. Two of these, the Ashy and the Ocellated Geckos, are considered established alien species. The third, the Reef Gecko, is thought to be a native form.

Jake and I had driven to the Lower Keys (this term means south of the 7 Mile Bridge) for an entirely different reason, but since we had a bit of spare time, when Jake said he’d like to find a hatchling Ashy Gecko a quick look seemed to mesh well with our later plans. Jake had already found numerous examples of the plain-colored adult Ashys, but the beautifully colored hatchlings had managed to evade his efforts.

Ashy geckos are secretive but common denizens of many microhabitats in the Keys. The 2-and-a-half inch long lizards may be found in the boots of palm trees, beneath all manner of surface debris, under garden rocks, in houses and sheds, and between the layers of fallen leaves.

It was the latter habitat that we decided to try. Within minutes, that we were in the right habitat for adult Ashy Geckos was quickly evident. With them we found snails, scorpions, Amerafrican house geckos, and an abundance of tiny food insects.

Although I had found several hatchlings on earlier trips, it took more than a half an hour of looking before Jake found the first and only hatchling seen on this effort. It was beneath a few fallen leaves at the very edge of a busy trail. Success!

Wednesday, July 3 2013

When you decide you'd like to set up a terrarium for your reptiles, you can go for a simple set-up or one that's considerably more complex.

The simple set-up is basically a monastic cell, with newspaper/paper towels on the bottom, a plastic hide box and a water container. Easy to set up, easy to maintain.

If the idea of looking at something so unadorned doesn't appeal to you (or if you figure your pet desires more than the least you can provide), you can put more effort into the setup and create something more naturalistic.

Tuesday, July 2 2013

Departure day had caught up with us, and departure time was approaching rapidly. We had a couple of hours left until checkout, so we decided to take one more stroll to a couple of South Bimini locales.

Destination, the vicinity of a well that actually held a little water.

We had little hope of completing our “Herps found on Bimini” checklist, but there was a chance of finding one or two additional taxa. And that was exactly what we accomplished.

More greenhouse frogs, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, an adult Cuban treefrog, Osteopilus septentrionalis, dozens of Cuban treefrog tadpoles, and many hermit crabs were added to our lists.

Thursday, June 27 2013

We began the next morning of our Bimini reunion by seeking additional Bimini Green Anoles.

We hoped, but failed, to photograph a displaying male. Bimini curlytails were already out sunning on sidewalks and garden walls. The cross-channel ferry to the South Island was nearing. It was our plan to return to the airport and work our way southward to the tip of the island, searching for twig (also called ghost) anoles, geckos and whatever else we could find.

As it turned out the twig anoles, Anolis angusticeps oligaspis, were rather easily found as they thermoregulated in the morning sunshine at the tips of slender, sparsely leafed, twigs.

Tuesday, June 25 2013

My yard in Ft. Myers, FL, was well-populated with Green Anoles, Anolis carolinensis. Although most males that I saw had dewlaps of bright pinkish red, dewlaps that I then referred to as “normal” a small percentage had dewlaps of greenish-white, gray, grayish green, or (I suspected) when a normal and a gray interbred the dewlap would be pale pink broadly edged with gray or white.

But if the dewlap wasn’t normal then the lizards were referred to as “abnormals.” But truthfully, I never thought too much about the dewlap color. I just enjoyed the lizards for what they were.

Then in 1991 the unthinkable happened. In the Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society, Thomas Vance elevated these gray throats to subspecies status and dubbed them Anolis carolinensis seminolus.

I was perplexed by this listing then and remain so today, for as I understood the subspecies concept (and I am a believer in subspecies), two subspecies could not populate the self same niche, and to qualify as a subspecies 75 percent of a population must display the stated characteristics.

Monday, June 24 2013

Responsible herpers in the West Fargo have been working for twelve months to rewrite a city ordinance prohibiting large constricting snake species.

The ordeal began in July of 2012, when a man brought his 8’ Burmese python into a public park and the police informed him it was illegal for the snake to be in the city. This triggered a reaction that brought to light an unregulated ordinance that banned “any poisonous, venomous, constricting or inherently dangerous member of the reptile or amphibian families.” The city’s police chief stated than he was not a fan of snakes and the mayor has similar feelings. The city officials were initially against changing the ordinance but the reptile folks have won the fight.

The python owner originally addressed the city council at the first open meeting following the incident and failed to receive a majority vote. At the next city meeting, dedicated reptile keepers and members of the Fargo Herpetological Society, with assistance from the National Herpetological Congress, addressed the ordinance in a professional manner and began the process of revising the ordinance with the city officials.

After months of work with an anti-reptile city board, the largest species of snakes are now allowed in the city on a permitted system. The herp community in West Fargo could have been inactive and left the original ordinance in place, but by educating the city officials and putting forth some effort, they now have the opportunity to keep large constrictors.

Continue reading "Herpers work with city to rewrite ordinance"

Thursday, June 20 2013

Although Jake and I both live in Florida and thought that we were rather used to the heat of summer, we both found the lack of available shade on Bimini a bit disconcerting. True, there was always the dense scrubby woodlands, but these were so amply packed with poisonwood (to which we are both very allergic) that neither of us chose to spend much time therein. The lack of transportation on South Bimini was also taking its toll. Departure time was drawing ever nearer and we were still nine taxa short of our goal.

Then came a bit of good luck. Asked by a store owner what we were doing on South Bimini, we explained that we were photographing reptiles but weren’t having the best of luck.

His response was “Look up Jack and Jill (fictitious names as I don’t know whether they would choose to be identified). They know all about the reptiles here.” So that afternoon we did just that. Not only did these kind folks allow us to photo a Bimini Boa, Epicrates striatus fosteri, that was temporarily in their keeping, but they provided a few locales for us to check that evening.

So after supper, as darkness enveloped us and the BSDs (blood-sucking dipterids in the forms of mosquitos and no-see-ums) came out to play, we were back on South Bimini.

Wednesday, June 19 2013

My first tokay gecko was purchased on a whim. I was living in Albuquerque, NM, just out of college, living back home while looking for work with no idea of where I'd end up. I made one of my regular trips into the only pet store in town that sold reptiles, and came eyeball to eyeball with a tokay gecko.

For someone whose lifetime experience with lizards had been limited to whiptails and what we called sand lizards ( Uta sp.) the tokay was breathtaking. Money changed hands (I think the gecko cost $6.95) and I went home, proudly bearing my new treasure in a brown paper bag. I had a glass-fronted cage made from a dresser drawer leftover from my high school days, so I dug the cage out and set it up. I opened the bag with the gecko inside and placed it inside the cage. Pretty soon Fido Fidas Fidarae, Fido for short, came out of the bag and clung enchantingly to the back wall of the cage. I sat and watched him. He was something to look at, grey with powdered blue and deep red tubercles.

I knew nothing about geckos, and no idea Fido was nocturnal, although his large eyes gave me a basic clue. When he didn't immediately drink from his water dish, I was worried because I knew that reptiles need water. I opened the cage, covered my hand with a hand towel (I'd been bitten by race runners and knew lizards could nip) and picked him up. I offered him fresh cool water, streaming from the bathroom sink. He thanked me by turning inside the towel and latching onto the very end of my index finger. I saw stars. I tried to free my finger by pulling gently. He tightened down so hard his eyeballs sank in. I took him into the utility room and tried to gently pry his mouth open with a screwdriver. His jaw bent alarmingly and his eyeballs sunk in.

The two of us wandered around the house, my free hand supporting the lizard/hand/towel combination. I wondered what to do next, imagining the lizard as part of a bridal bouquet. I didn't even have a boyfriend at the time, but it was beginning to feel as if this lizard was going to be a permanent attachment. I returned to the bathroom sink, filled it partially with cool water, and stuck my lizardhand, already a single word in my vernacular, into the water. To my numbed delight, Fido let go. I drained the sink, covered him with the towel, and picked him up carefully and returned him to his house.

I moved to Florida a few months later, and Fido went with me. He lived for years, drinking sprayed-in water droplets from the sides of his tank and feeding on thawed, frozen mice. He took them with such intensity his eyeballs sank in, and it always made me flinch.

Things turned out OK for me and Fido, but the moral of this story is simply know what you're getting into before you plunk down your cash.

Your fingertips may thank you.

Continue reading "Tokay gecko: Knowing what to expect"

Tuesday, June 18 2013

Of the four anole species on Bimini, the twig or ghost anole is the most diverse and the most difficult to find.

This attenuate brownish gray, sharp-nosed, anole is very arboreal and prefers to move slowly and stealthily. The male’s dewlap is a pale yellowish peach and does not seem to be distended as readily as the dewlaps of most species. If approached, the twig anole will quietly and slowly sidle around the branch on which it is resting, adroitly keeping the branch between itself and the observer. The grayish coloration and lineate pattern blend so well with the bark of the trees on which this anole lives that the lizard is very easily overlooked.

In 1948, based on cranial scalation and lamellae count, Jim Oliver thought the Bimini twig anoles sufficiently distinct from those on Cuba and elsewhere in the Bahamas to assign them their own subspecies. He named them Anolis angusticeps chickcharnyi, the subspecific name being based on a mythical being -- a ghost, if you will, or perhaps a goblin -- that supposedly appeared on Andros Island.

Thursday, June 13 2013

Our plan was to take a taxi to the South Bimini Airport and walk the several miles back to the ferry slip when we wished to return to the hotel. The taxi ride was fine, the walk back was horrid.

Near the airport we encountered numbers of Bimini Whiptails, Ameiva auberi richmondi. I recalled that the last time I had visited the island I had been able to run this speedy, alert, taxon down. This time though? Not a chance. Had something to do with advancing age — mine, not the lizards.

Tuesday, June 11 2013

Two and a half hours after departing Miami, the ferry gently nudges the dock on North Bimini. This was Jake Scott’s first trip and the first time I had visited since 1973—40 years prior. On that earlier venture I had found every one of the 16 species of reptiles and amphibians (with the establishing of the Amerafrican House Gecko there are now 17 taxa) in less than a day of looking. I couldn’t help but wondering what changes had been wrought in the ensuing four decades.

Disembarking, clearing customs and immigration, and checking into the hotel took less than a half an hour. Even before we had cleared customs we had seen the first lizard species, the Bimini Curly-tail, Leiocephalus carinatus coryi.

Friday, June 7 2013

Can herpers fight back and win against unfair legislation targeting our animals? Yes, if you do it right!

Scott Snowden faced new legislation that would have made his pets illegal. A city ordinance was proposed concerning dogs with language attached that would have banned all constricting snakes.

Scott stepped up, addressed the issue and was successful by educating the city officials. His professionalism and dedication were rewarded. Thanks to everyone who supported Scott and thank you, Scott, for being an inspiration to the herp community.

A personal letter from Scott Snowden:

My family and I cannot thank USARK and its members nationwide enough for coming to the aid of responsible snake owners in the Montana town of Laurel. I first contacted USARK on February 28th after learning that our city council was attempting to put language that would ban all constricting snakes within city limits to a proposed dog ordinance. USARK President Phil Goss greatly supported my efforts and spoke with me several times via phone and email. USARK responded with a national alert and a link that sent emails from all across the nation to our town’s elected officials. I also spoke before city council, stating our case and asking them to simply follow the existing state laws that govern prohibited species. I spoke to the head of the safety services committee last week and learned that the ordinance has been sent to the legal advisers with NEW language that complies with the state law and does not put a blanket ban on all constricting snake species. He cited the significant public outcry as playing a key role in their decision to modify the ordinance’s language. Thank You! We won’t be totally out of the woods until the ordinance is presented back to the city council, ratified, and signed by the mayor, so we are staying vigilant in our monitoring it. That said, we are taking a moment to celebrate and say thank you to everyone that has supported us!

Sincerely,

Scott, Mandy, & Kiara Snowden

Continue reading "Stopping bad herp laws? Yes, you can!"

|