Reptile & Amphibian

News Blog

Keep up with news and features of interest to the reptile and amphibian community on the kingsnake.com blog. We cover breaking stories from the mainstream and scientific media, user-submitted photos and videos, and feature articles and photos by Jeff Barringer, Richard Bartlett, and other herpetologists and herpetoculturists.

Friday, December 30 2016

Peninsula ribbons seem to outnumber the more northerly blue striped subspecies at Gulf Hammock.

Kenny and I were on a very rural dirt road that is well within an area known as a stronghold for classic “Gulf Hammock” rat snakes the target of that nights search. The total rat snakes found, despite seemingly ideal field conditions, was a resounding zero. But despite the lack of rat snakes we were far from skunked! On both the sand roads and later, on the paved roads, venomous snakes were on the prowl that evening. On the sand roads we found 4 dusky pygmy rattlers, Sistrurus miliarius barbouri, and 2 small Florida cottonmouths, Agkistrodon piscivorous conanti. On the paved roads we added 1 larger (3+ feet) Florida cottonmouths and a single Peninsula ribbon snake, Thamnophis sauritue sackenii, to the evenings total. We left happy, knowing then that we’d be back to try again tomorrow.

Continue reading "Gulf Hammock of Florida"

Thursday, December 29 2016

This Suwannee alligator snapper had a 6" carapace length.

Ever get smacked in the headlamp on a dark night by a big water snake that you didn’t know was there? I’ll tell you, it can really catch your attention!

The Santa Fe River was either at its all time lowest or darn close to it. Normally 4 or 5 feet deep at this locale, at the time in question you could then wade across the river without getting much more than your ankles wet! Did I mention that we were in a drought—a drought that showed no sign of easing. I was searching for Suwannee Alligator Snappers, Macroclemys suwanniensis.

The biggest of the alligator snapping turtles stayed pretty close to the deeper pits scoured around old snags and root systems. Smaller snappers, more mobile, hence less restricted, could still be seen in shallower areas. And it was one of these smaller turtles, one about 6 inches long, that I was trying to photograph in situ when I blundered into a big—or at least when it struck at me it seemed big—brown water snake, Nerodia taxispilota.

It was well after dark and I was intent on following a turtle that was at least equally intent on not being followed. In fact, the turtle had just disappeared, having maneuvered quickly into a hidden root system in the undercut bank. Without first looking I leaned against an overhanging limb to stablize myself as I searched (in vain, I might add) and accidentally pinned the water snake against the tree with my shoulder. As water snakes are wont to do, this one (all 3 ½ feet of it—adults can be 5 to 5 ½ feet in total length) took exception to my accidental familiarity, striking at the illuminated and moving headlamp.

I jumped back, tripped, fell (sure glad the river was low!) saw the snake drop into the current, and decided to call it quits. Now, which way was the car?

Continue reading " Snappers and Brown Waters on the Santa Fe"

Wednesday, December 28 2016

As in many other locales in Texas, rocky roadcuts between Sanderson and Comstock provide ideal habitat for many herps. Though rainy and dreary as we drove it in 2016, this stretch of highway holds many fond memories.

Jake and I had been in West Texas (Comstock to Big Bend) for more than a week and had been plagued by adverse weather for all but one night. Deluges had curtailed most herp movement for the first 2 nights. This was followed by a high pressure system for the next 6 nights. Jake’s vacation time was quickly drawing to a close, and we were still experiencing bad weather. Hoping to find a particular taxon of earless lizard and to make the most of the persistent high pressure we had elected to head back eastward a day early. By the time we had gotten to Sanderson the sunshine had been obliterated by sullen clouds that stretched to the horizon. The road, somewhere just east of Langtry was wet and a gentle rain was still falling —it too stretching to the eastern horizon. Obliterated with the sunshine was the lizard search.

I would imagine that unless you’re a herper or a birder, the long drive from Sanderson to Del Rio, might be a boring strip of road. Occasional cattle, a raven or two, and a dozen or so 18-wheelers—a roadsign directing you to Pumpville, another for Pandale, the communities of Langtry and Comstock, and a vast reservoir are all you will see.

But for herpers this same stretch of road holds many possibilities, especially if traversed on a dark night during a period of low barometric pressure. For, to many of us, and certainly to me, this is “the gray-banded kingsnake road.” It was from beneath a cattle guard at the corner where Bill Chamberlain’s gas station once stood that with Gordy and Dennie I was to see our first “Blair’s king,” a dark phase (yes, they WERE Blair’s kings back then). And then, just to add to the excitement of that night,on one of the dirt roads (I think it was the road to Pumpville) we found a second Blair’s, a light phase. Although I’ve never duplicated that 2 in one night episode, I’ve added rat snakes, long-nosed snakes, rattlesnakes, and many others to the species found along US90.

Bored by this road? Not I!

Continue reading "Sanderson to Comstock—Memories"

Tuesday, December 27 2016

As hatchlings, alligators are prominently banded with yellow on black.

Alligators are very much a fact of life in the deep south. And our area of Florida is certainly not exempt. We live between a fair-sized pond and a sizable wetland. Just beyond the wetland is Paynes Prairie State Biological Preserve. There is no shortage of gators here. In wandering from pond to wetlands or vice versa gators often stop in our yard. So far he visitors have ranged from 14” to 8’. Because we have dogs the bigger alligators cause us some concern so we escort them out of the yard and at least part way back to the pond. So far none have returned.

Since the wetlands opened across the street from us we have been able to watch and listen to these big reptiles at about any time we choose. Breeding activity (including male bellowing) and territorial skirmishes are seen and heard in April and May. Hatchlings are usually first seen in late May to July. Except on the most inclement of winter days basking adults may be seen year round.

As stated at the outset, gators are very much a fact of life here. We keep our distance and during the breeding season we keep even greater distances from displaying males and nesting females. Dogs on trails, even when on leashes, can lead to seriously adverse gator encounters. Pure and simple, dogs = food. Watch toddlers carefully. Use common sense folks. Gators are big, dominant, predators that often feed in the shallows or on the shoreline. Give them their due! As the cliché states, “Be safe, not sorry!” And I’ll add, if you really love your dog, leave it at home when you’re in gator country.

Continue reading "Alligators?—Ho Hum."

Monday, December 26 2016

Hatchling Texas alligator lizards are prominently marked.

The family Anguidae comprises species from Europe, Africa, Mexico, Asia and the United States. Several of the species are limbless and others, such as the various alligator lizards, have short but fully functional limbs. All have functional eyelids, most have a lateral groove, and the broad tongue is protrusible and bears a slight notch at the tip.

To many hobbyists, the Texas alligator lizard, Gerrhonotus liocephalus infernalis--attenuate, short limbed, and long-tailed--is the king of the family. Certainly it is an interesting species that, although not rare, is secretive and can be difficult to find. Although essentially terrestrial, hiding beneath all manner of surface debris (leaf litter, logs, rocks, cardboard, etc.), this lizard is quite capable of climbing and may ascend juniper or other rough barked trees/shrubs.

Adults of this impressive lizard are gray(ish) or brown(ish) with poorly defined lighter dorsal barring from nape to tailtip. The ground color of juveniles (and hatchlings especially) is much darker and the dorsal barring is lighter and more precise. The long tail is slightly prehensile and readily autotomized.

This is a lizard of Texas’s Edwards Plateau westward to the Big Bend region and from there southward to San Luis Potosi.

Continue reading "Texas Alligator Lizard"

Friday, December 23 2016

Big, loud, prolific, and predatory describe the adult bullfrog well.

Besides the painted turtles mentioned in my last blog, the ponds in the one-time zoo in my hometown had a sizable (both in numbers and body size) and vocal population of bullfrogs, Rana catesbeiana. In itself this was not unusual. By definition bullfrogs are big, noisy, and prolific. Having a body size of 8+ inches, males of this very aquatic species are larger than females. And although females are capable of making escape and fright screams, it is the males that produce the more typical croaks, bellows, and “jug-o-rums.” That takes care of the big and noisy parts of my above statement, but how about prolific? Female bullfrogs produce egg masses that contain from about 7,500 eggs to more than 25,000! That, my friends, is prolific! Fortunately, many predators, from cats to raccoons to herons to water snakes, to bigger bullfrogs to aquatic insects consider bullfrog tadpoles and metamorphs a tasty repast, so not all young bullfrogs make it to the adult size. In fact, it is probable the most don’t survive past the juvenile/subadult stages.

But what about those that do? Well, back to the bullfrogs in my hometown zoo ponds where, secluded and protected by lush water lily/lotus growth dozens (if not hundreds) of wee bullfrogs evaded predation, survived and grew and grew. Most of the froglets were normal, but I would find a few—1 or 2—each year that had a similar deformity—3 hind legs! Cause? Unknown. And I never found an adult with this anomaly.

Continue reading "A Mention of Bullfrogs"

Thursday, December 22 2016

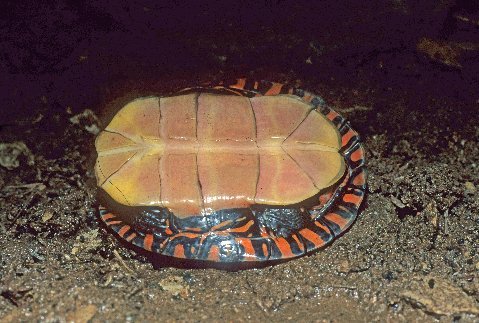

Eastern painted turtles usually have an immaculate plastron.

Midland, Eastern, or Intergrade? That is the question.

As a kid I was either skipping school to watch a warbler migration or out bugging the local (Springfield, MA) herp populations. It seemed then that either of these pursuits was a whole lot better than sitting in a classroom.

One of the herp populations that I enjoyed visiting was the huge population of painted turtles in the water lily/lotus ponds of erstwhile local park/zoo, i.e. Forest Park. I didn’t know much about herps back in those early days (I’m not sure I do now!) but I did know that there was a dramatically different suite of characteristics in those turtles. Some had plain yellow plastrons, some had plastrons smudged with dark pigment, and the plastron of others bore a well-defined central figure. I also noticed at some point in time that the carapacial scute sutures (costals and vertebrals) of those having the solid yellow plastrons went nearly straight across the carapace from side to side (excluding the marginals) while the costal sutures of the painted turtles with the plastral figures were not in line with the vertebral sutures. I don’t remember the carapacial suture configuration on the turtles with the smudged plastrons.

So, what did we have in these painted turtles? Employing the description still used today we had eastern painteds, Chrysemys picta picta (solid yellow plastron and nearly straight side to side scute sutures), midland painteds, C. p. marginata (well defined plastral figure and offset costal-vertebral sutures) and intergrades (smudged plastrons).

And therein lies the problem, a problem unbeknownst to me then, and of no interest to the turtles either then or now. But while the easterns and even the intergrades could be easily explained, the presence of 2 well defined subspecies, the eastern and the midland, in the same puddles should not have occurred. Could our descriptive criteria be faulty? Awww heck. As long as the turtles don’t care why should it bother us.

Continue reading "Painted Turtles: Midland, Eastern, or Intergrade?"

Wednesday, December 21 2016

Hatchling rusty whipsnakes are bright green.

Most herpers are familiar with the ontogenetic changes (orange as neonates/hatchlings and green as adults) of emerald tree boas and green tree pythons. But fewer among us are familiar with the color changes of the rusty whipsnake, Chironius scurrulus.

The rusty whipsnake is a hefty and often feisty Amazonian species. Although 4 to 5 feet in length is the most commonly seen adult size, a few may exceed 6 feet by a few inches. Subadults and adults are often found along watercourses where they feed on amphibians and (I have been told but have not verified) fish. The term “rusty” fits the adults to a T—they are a rusty orange, often with scattered black scales dorsally and laterally. The head may have a dusky hue.

The hatchlings, however, are semiarboreal and are a beautiful leaf green. The green dulls quickly with age and growth and within 2 or 3 shedding cycles the once bright green baby has become a dull olive, an ontogeny 180 degrees reversed from the better known emerald boas and pythons.

Continue reading " Reversed Ontogeny"

Tuesday, December 20 2016

Once common, today the Tucson shovel nosed snake, C. o. klauberi, can be difficult to find.

The insectivorous (some arachnids are also eaten) genus Chionactis, the shovel-nosed snakes, contains 2 fossorial species, palarostris and occipitalis. The former, the Sonoran shovel-nose, Chionactis palarostris, contains 2 subspecies ( palarostris and organica) while the western shovelnose, C. occipitalis, contains 4 ( occipitalis, annulata, klauberi, and talpina) .

The ground color of both species is white (or cream or yellow), with well separated saddles of black or brown and (often) saddles, or at least a hint, of red (or orange) alternating with the black. Some saddles, especially the dark ones, may extend ventrally and encircle the body. Colors and patterns vary both subspecifically and individually.

These small (14-17 inches), slender, burrowers feed on insects and arachnids. Seldom seen (unless flipped) by day, they are often found above ground at night and can be remarkably abundant when atmospheric conditions are ideal.

Rarely seen in the United States, the range of Chionactis palarostris, includes nwSN and extreme scAZ. Conversely, C. occipitalis, the western shovel-nose, ranges primarily in the sw USA (scAZ and scCA northward to sNV), entering MX only in nBaja and nwSN.

Continue reading " Shovel-nosed Snakes, Fossorial Beauties"

Monday, December 19 2016

Habitat of the Chihuahuan Lyre Snake in West Texas

That Trimorphodon vilkinsonii are out there, there is no doubt—no doubt at all. There is also not the least bit of doubt that I can’t find them. Others find them, sometimes mere minutes before I arrive or after I have left. I know this for a fact for sometimes I’ve been allowed to photo the found snake.

I began looking for this elusive nocturnal snake on Texas trips in the ‘50s with my friend and mentor, Gordy (E. Gordon) Johnston. We drove (actually Gordy drove and I rode) back and forth, and failed to find them. Subsequently I have failed to find them on many of the same roads, right up until today, some 55 years later. If not anything else, at least I am consistent—except for one time. That one time about 15 years ago, Kenny and I were driving through the Chinati Mountain ghost town of Shafter, Texas. In the middle of the town (population once about 4,000, now about 11) we found a DOR lyre snake. The DOR snake was rather fresh and I wondered where the car that had killed it had come from, where it was going, and if the killing of the snake had been deliberate or accidental. It just seemed impossible that with that little traffic the paths of car and snake should have crossed.

Since then I have looked with reasonable regularity during all kinds of weather at all hours of darkness, and never again glimpsed one. Hugh tells me they’re fairly common. Ron tells me they’re very rare. I know only that I have driven and walked the rockcuts in their known TX range for more than half a century and have not only failed to find them, but failed dismally. Time to switch to birding .

Continue reading "Chihuahuan Lyre Snake—A Lament"

Thursday, December 15 2016

The question--will ontogenetic changes turn this little western coachwhip pink?

One of the most noteworthy snake features of the Big Bend region is to be found on adult western coachwhips, Masticophis (you are free to call them Coluber if you choose!) flagellum testaceus. The adults assume a bright (some call it “screaming”) pink coloration. The juveniles—up to at least a 3 foot length—are typically a straw tan with broad, light, bands.

Coachwhips and the related whipsnakes are usually very evident in the Big Bend region. Since both Jake and I hoped to surprise and photograph one of the pink adults, we made a point of searching for them on several mornings. On most of those days we drove for at least 50 miles on our searches, and on one occasion we drove for more than 200 miles. Zero coachwhips, zero whipsnakes. If you’re thinking “what a failure,” just imagine how we felt. We had failed to find one of the most conspicuous and commonest of Big Bend’s diurnally active snakes. This stationary high pressure system was really crimping our style (and our hopes). With our allocated trip duration quickly drawing to a close we decided to move up to northeastern Presidio County. Could (or would) a change of venue make a difference in our success (or lack of same)?

Did it make a difference? Well, we at least saw a coachwhip—a straw colored juvie-- streaking across the roadway. We saw Texas horned lizards and lesser earless lizards. We saw desert box turtles. And we saw Ron and Daniel Tremper who had just seen an adult pink colored coachwhip cross the roadway and stage one of their oft-duplicated yet always surprising disappearing acts—probably by scooting down a ground squirrel hole.

But, and for us this was an important “but,” Ron and Daniel presented to us without ceremony a 30” western coachwhip that they had chased down (all I can say is a respectful “WOW”). It now sits in a place of honor as the only snake in my very small herp collection. I get bitten by it almost every day but I’m hoping that as it grows and if it drinks enough blood it will assume the beautiful pink of its Presidio County brethren. I’ve gotta get that picture somehow! Thanks, Ron and Daniel. I’ll keep you posted on the ontogenetic changes—if any.

Continue reading "Pink Coachwhips"

Wednesday, December 14 2016

Trans-Pecos rat snakes were the species most commonly seen.

With several mobile homes (cabins) scattered over the hilly terrain, and having a herp-friendly owner, Wild Horse Station is a magnet for herpers and birders. Although Jake and I had failed to make reservations earlier, we had lucked out. Mrs. Hammer (owner) still had one unrented cabin. We rented it and decided on an afternoon nap to prepare us for a night of herping.

Although it had poured here the night before we arrived, the low pressure system had then been replaced by a high that was to persist for the 5 days we were in the Study Butte-Terlingua region. Weatherwise, things did not look overwhelmingly in our favor for snake movement. But after having driven 1500 miles with high hopes firmly entrenched, adversity is difficult if not impossible to accept.

So anyway, here we were, still with high hopes, at Wild Horse Station for 5 days. Luckily, our friends from last year, Charles and Wendy Triche, were in the next cabin so we could visit and commiserate.

The nights cooled quickly allowing the few snakes that were out and about to move shortly after nightfall. But let me tell you how bad conditions (I really don’t think it was our searching techniques!) were; on a 30-mile stretch of road where we usually see a dozen or more rattlesnakes of 4 taxa, in 5 nights we saw ZERO, and on that whole trip we saw only a half dozen Trans-Pecos rat snakes! Even the prey items, the pocket mice, kangaroo rats, and other desert rodents, were at an all time low.

The half dozen Trans-Pecos rat snakes, Bogertophis subocularis, we found were all normals (no blondes, but Bob Hansen’ s group found a blonde the night after we moved northward—congratulations Bob and gang). The few variable ground snakes, Sonora semiannulata, found were pretty but none were of the more colorful banded phases. And after dozens of runs and rock checks through prime habitat, finding our principal target taxon, a Chihuahuan lyre snake, Trimorphodon vilkinsonii, remained only a dream.

Will there be a trip next year? Only time will tell. If so will it show better results. Only Mother Nature and Jupiter (the God of weather) can say.

Continue reading "Wild Horse Station"

Tuesday, December 13 2016

Although a cool morning, eastern collared lizards were up and active.

On our second night in Comstock we were treated to more rains and the only significant find was a DOR Baird’s rat snake. It was time to head west again. Radar showed clearing weather and the forecast in the Davis Mountains was for several days of hot, clear, high-pressure, weather. From one extreme to the other with neither evening downpours nor stationary high pressure systems being exactly conducive to herp activity.

The stop at Davis Mountains State Park was actually a birding stop with elf owls and Montezuma quail being the target species. But with that having been said, neither Jake nor I are exactly adverse to happening across herps of any species.

While searching out the owl, a pair of Texas whiptails, Aspidoscelis gularis, busily searched out insects. During the longer search for the quail we happened across both a foraging eastern collared lizard. Crotaphytus collaris, and startled an almost fully grown Great Plains skink, Plestiodon obsoletus. This was a lifer for Jake who spent a half an hour following the skink, camera in hand. Again, time for a nap in preparation for a night of road-cruising.

Continue reading " West of Comstock"

Monday, December 12 2016

These 3 Trans-Pecos copperheads were found on this trip.

Our plans again changed, but only by a few minutes. The hour was late and we had decided to call it a night. Then, well on our way to the road exit, I decided “aww heck. Just one more pass and then we’d leave. I reversed direction again and had hardly gotten up to cruising speed when “SNAKE.” I slammed the brakes on and Jake was out of his door before the car fully stopped. Another “WAHOOOOO,” then “Copperhead.”

This, the Trans-Pecos copperhead, Agkistrodon piscivorous pictigaster (and yes, I’m aware of the nomenclatural changes but I happen to believe in the subspecies concept!) was another lifer for Jake.

This, the southwesternmost of the 5 subspecies of copperhead, is also the most strikingly colored. The dark bands are wide, shade to a narrow rich mahogany edging fore and aft, and contain a central light patch as they near the dark belly. Pretty? You have to see and adult example (juveniles are paler overall) of this pit viper to fully appreciate its beauty.

And we were able to appreciate it 3 times, for besides Jake’s lifer, we found 2 additional copperheads. Things were looking up. Now on to Study Butte.

Continue reading " One more for Jeff Davis County!"

|