Fall Feature, 1998

The zonatas of Washington and northern Oregon Photo, right, by U.S. Forestry Service; Columbia River Gorge |

|

Part I.

| In Washington, Lampropeltis zonata populations occur mainly along the Columbia River Gorge, on southern slopes of open canopy oak forests of the Cascade Range. Talus found at the base of rimrock cliffs also provides suitable habitat, presumably along with the rare fractured granite boulder croppings. |

|

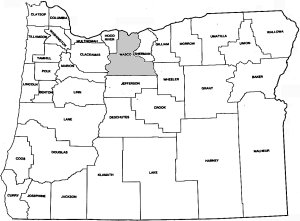

The snake has been thought of as extemely secretive and as existing at very low densities "because extensive field studies have found only a few individuals," reports the Washington State Gap Analysis. Literature records exist for two counties in Washington: Klickitat Co., and Skamania Co. A single record exists for central Takamia Co. Additionally, M. L. Johnson (1939) listed a reported presence of zonata in southeastern Washington, outside of the Cascades; however no specimens exist to verify this report. Such presence seems illogical.

|

|

In questioning Stebbins' record for Wasco Co., Oregon (still published in the distribution map for L. zonata in his recent edition A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians ), the author examined habitat types of the Columbia River George counties in both Washington and Oregon. In plant association and topography, Wasco Co. presents much similarity to its Washington counterparts. However, the Oregon slopes immediate to the Columbia River consisited mainly of shaded, moist coniferous forests with heavy fern undergrowth and fallen trees. In other areas, impassable sheer rock ridges and exposed mountainside rock slides--devoid of much plant cover--dominated. Neither habitat type looked conducive for housing colonies of zonatas , at least compared to the areas they occupy in Washington. Heading south, the habitat improved, resembling seral stages of open and closed canopy deciduous and coniferous forest. Adequate rock cover consisted of small talus areas sheltered peripherally with vegetation.

In order to understand the fragmentation of L. zonata , the enthusiast must understand how such distribution came about. Saving any in-depth explanation, the fact snakes can only migrate over contiguous regions dictates that a region containing a disjunct population must have been at one time continous with other population-containing regions. This can be explained by the fact that during historic geologic and climatic changes, life zones either expanded or restriced, allowing the species of that life zone to either migrate outward in continuum with the expansion or by forcing it to become further restricted. Additionally, younger forms invading the same life zones pressured more primative populations. Such reptile populations faced further restriction, outcompeted for food by newer, more efficient forms. Regions of displacement afforded the older species a foothold, where primative characteristics afforded some advantage in that habitat.

In regards to the northern zonata , the species must have transitionally migrated north of its center of orgin, meaning that at one point or another the Washington populations existed continuously with more southerly populations. Climatic change then destroyed forest continuity, forcing forest segments to retreat. Such sementation isolation best describes the pattern of distribution in zonata . By the same line of reasoning, it seems logical that in the Cascade range, zonata could have maintained a foothold in northern Oregon, immediate to the Washington populations. The similar regions experienced similar geologic and climatic forces; zonata occured there historically. Likely, northerly populations of zonata will be documented in Oregon.

Part II and pictures forthcoming.